Infant Anaphylaxis: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Guide

Infant anaphylaxis is a serious allergic reaction occurring in children from birth to age 1. It is a potentially life-threatening condition. Anaphylaxis can develop fast and affect one or more organ systems. These may include the skin, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal system, cardiovascular system and neurological system.

Anaphylaxis is relatively rare in infants, but it does happen. Prompt recognition of symptoms and fast treatment with epinephrine is essential.

“When it comes to recognizing a serious allergic reaction in a baby, it’s helpful to keep a few things in mind,” says pediatric allergist Michael Pistiner, MD, MMSc, Director of Food Allergy Advocacy, Education and Prevention at the Food Allergy Center at Mass General Brigham for Children in Boston. “Unlike older children or adults, they can’t tell us what they are feeling because they are nonverbal. So, we will need to know what signs and symptoms to look for. Also, infants and toddlers may have certain behaviors that can overlap with symptoms and signs of allergic reactions, both mild and severe.”

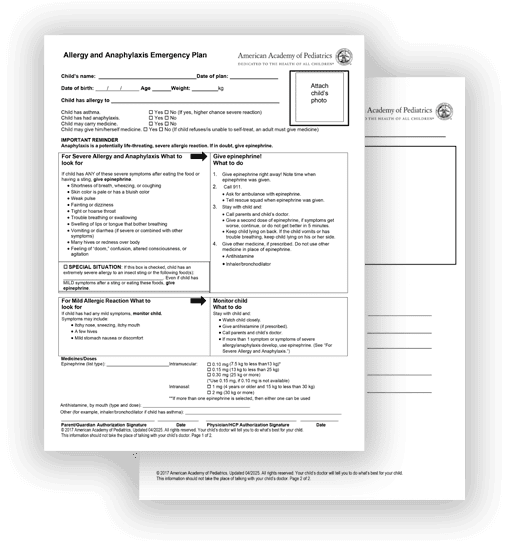

Get started with preventing and treating anaphylaxis with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Allergy and Anaphylaxis Emergency Plan.

What is the cause of anaphylaxis in infants?

A serious or severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) in babies and infants is similar to what occurs in older kids and adults. It happens when the immune system (the body’s defense system for germs and other invaders) thinks a certain substance (in most cases, a protein) is dangerous.

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies bind to the food protein and trigger the allergic reaction. It results in the release of histamine and other chemicals into the surrounding areas and potentially throughout the body. This causes the cascade of symptoms that is known as anaphylaxis.

Food is the most common cause of severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) in infants.

How to distinguish anaphylaxis from a mild allergic reaction

Both are allergic reactions from an immune response. But anaphylaxis is a more severe and potentially life-threatening event. It happens fast and can involve multiple organ systems. A serious reaction may impact the skin, respiratory system, digestive system, neurological system and/or the heart. If left untreated, anaphylaxis can lead to airway compromise or shock.

Not all signs and/or symptoms are obvious. The level of severity from a reaction can change quickly and become life-threatening. If an allergic reaction includes severe signs and symptoms, or signs and symptoms in more than one body system, then consider the reaction serious. Consider the reaction anaphylaxis.

Serious allergic reactions require immediate treatment with epinephrine as a first-line intervention. Epinephrine is safe and works quickly. Early treatment can keep a reaction from getting worse.

Allergic triggers in babies

Food, medication, insect venom and latex are allergens that can trigger anaphylaxis – not only in infants but all age groups.

Food allergies in infants

Food allergies are the most common cause of anaphylaxis in young children. Symptoms occur when a baby consumes an allergen. The baby’s body mistakenly identifies it as harmful, leading to the allergic reaction.

- Infant allergy to milk. Cow’s milk allergy is often cited as the most common food allergy in infancy. It affects an estimated 2% to 3% of babies. Many children outgrow cow’s milk allergy by ages 3 to 5, though some may remain allergic lifelong.

- Infant allergy to formula. An allergy to formula often stems from cow’s milk protein. Some infants may also react to specialized formulas containing different protein sources. These formulas usually have partially or extensively hydrolyzed proteins aimed at reducing allergens. But they can retain residual amounts. Some sensitive infants may still react to these remnants.

- Infant allergy to breast milk. This is a rare true allergy. Infants may develop symptoms after the mother consumes allergenic foods that pass into her breast milk.

- Infant allergic reaction to eggs. Egg allergies can be one of the earliest allergies that an infant develops. It can sometimes lead to severe reactions. Many children outgrow the allergy later in childhood.

- Peanut allergy and/or tree nut allergy in infants. Nut allergies are among the most common for many children. They carry a higher risk of serious allergic reactions, even in very small amounts. Peanut allergy and tree nut allergy tend to persist longer than milk or egg allergies.

- Other food allergens for babies. Although less common, wheat, soy, fish, and shellfish can also trigger reactions.

Medication allergies

Certain medications can cause anaphylaxis in infants. It occurs when the baby’s immune system identifies the drug as a harmful substance.

- Infant allergic reaction to amoxicillin or other penicillin-based antibiotics. These drugs can sometimes trigger severe allergic reactions in sensitive infants. If a baby has hives, swelling, or trouble breathing while on a medication, seek medical help immediately.

- Other medications. In rare cases, certain over-the-counter drugs or vaccines can induce anaphylaxis.

Other potential allergic triggers in babies

- Insect stings. Stings from bees, wasps, or other insects can trigger anaphylaxis. This is not common in early infancy.

- Latex allergy in babies. In rare cases, latex can cause serious allergic reactions in sensitive infants. Latex is in bottle nipples or pacifiers, as well as other rubbery products.

- Environmental allergens. In rare cases, seasonal or environmental allergens can trigger severe reactions. Allergens may include pollen, mold, pet dander, or pests such as dust mites, cockroaches or mice. These can also contribute to early allergy sensitization.

Signs of anaphylaxis in infants

Anaphylaxis in infants often appears different than in older children and adults. Recognizing signs of anaphylaxis in infants is critical.

Remember, infants cannot verbally communicate how they feel. Caregivers must be alert to physical and behavioral changes. Fussiness, refusal to eat, and/or swelling around the lips could be missed or mistaken for normal. There is also overlap of anaphylaxis symptoms with other behaviors commonly seen in infants.

Symptoms of anaphylaxis may vary among babies. And symptoms may differ for each time a baby has an allergic reaction. The severity of signs and symptoms can change quickly and, if left untreated, can become life-threatening.

While the underlying mechanism of anaphylaxis is similar for all age groups, anaphylaxis in infants often appears different than in older children and adults. In infants, the signs and symptoms may be more subtle and less obvious than in older age groups.

What does anaphylaxis look like in infants?

Signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis typically occur in more than one body system, no matter the age of the patient. These include the skin, respiratory, gastrointestinal or heart systems. It may also involve the neurologic system which can appear as a sudden change in behavior.

In infants and toddlers – unlike older children and adults – these signs and symptoms may be more challenging to detect. This is due in part to their inability to verbalize what they are feeling.

Important note: respiratory and/or heart symptoms can occur without obvious skin symptoms. If an infant eats a known allergen and respiratory or heart symptoms occur, you should consider that to be anaphylaxis.

If an allergic reaction includes severe symptoms or symptoms in more than one body system, treat with epinephrine right away. Epinephrine will help make a child feel better quickly and can keep a reaction from progressing. Remember: it’s epinephrine first, epinephrine fast.

Does infant anaphylaxis look different in people of color?

Hives from an allergic reaction may appear different in infants with darker skin tones. Signs such as changes in skin texture or a bluish or purplish tint may be present. (In people with lighter skin tones, hives appear as red.)

Awareness of these skin differences is critical for an accurate assessment of symptoms.

How to treat anaphylaxis in infants

Infant anaphylaxis is a medical emergency that requires immediate action. Epinephrine is the only medication that effectively treats anaphylaxis. It is the first-line treatment. You should always have at least two doses of epinephrine. It’s possible for anaphylaxis to come back, so a second dose is sometimes needed.

As soon as you suspect anaphylaxis, give epinephrine. Do this as soon as possible. Epinephrine auto-injectors are currently the primary delivery devices for children under age 4. Talk with your doctor to ensure you get the appropriate prescription for your child. Make sure you feel comfortable using the device and teach others how to use it.

How to give epinephrine to babies

Current guidelines stress that prompt use of epinephrine is critical in treating anaphylaxis and stopping severe symptoms. If there’s any doubt, don’t hesitate to use epinephrine. When administering epinephrine, follow guidance provided by healthcare professionals.

The primary epinephrine delivery device for pediatric patients under age 4 is the auto-injector. (An epinephrine nasal spray for children under the age of 4 is currently in development.)

Here are general instructions for administering an epinephrine auto-injector. Multiple brands are available and how they are administered will vary.

1- Prepare the auto-injector. Confirm the device is not expired and it is ready for use.

2- Administer the injection. Always follow the specific instructions provided with your epinephrine auto-injector:

- Hold your baby firmly but safely as you prepare to administer the injection. (You may need to help other caregivers learn the best way to hold your baby.)

- Hold the auto-injector in the hand that you normally write with.

- Remove the needle cap and then the safety cap from the prescribed auto-injector.

- Expose the infant’s outer thigh (it can be administered through clothing if necessary).

- Firmly press the device against the middle of the outer thigh at a 90-degree angle.

- Press the device until you hear a click, pop or beep. This confirms the injection is being delivered.

- Hold the device in place per the manufacturer’s recommended duration (2–10 seconds depending on the device). This ensures full delivery of the dose.

3- Post-injection actions. Remove the device and gently massage the injection site for about 10 seconds.

If symptoms improve after the first dose of epinephrine and your baby is feeling better, you may not need to go the hospital or emergency department. Discuss next steps with your healthcare provider.

However, you should call for emergency medical help or go to the hospital or clinic if…

- symptoms return or worsen after the first dose of epinephrine.

- your baby’s anaphylaxis is severe;

- symptoms do not go away promptly or completely after the first dose of epinephrine;

- you only have one epinephrine dose available.

A biphasic reaction is when anaphylaxis symptoms recur after initially improving. This can occur up to several hours later. It’s important to make sure you have two doses of epinephrine on hand. Sometimes a second dose is needed to treat a biphasic reaction.

If you only have one dose of epinephrine on hand, you may want to go to the hospital or emergency department to be safe.

What’s an Emergency Anaphylaxis Action Plan for infants?

An Emergency Anaphylaxis Action Plan outlines step-by-step instructions for managing a serious allergic reaction in an infant. The AAP uses an Allergy and Anaphylaxis Emergency Plan that is intended to be universal.

The action plans typically include:

- Allergen identification. A list of known triggers and how to avoid them.

- Symptom recognition. A description of early warning signs specific to infants. These may include fussiness, poor feeding, subtle swelling around the eyes or lips, or skin symptoms.

- Immediate response steps. Directions for rapid use of an epinephrine auto-injector and when to call emergency services.

- Proper positioning and monitoring. Guidelines on how to position the infant. Also how to monitor breathing, pulse, and overall condition until help arrives. Don’t hold the baby with the legs dangling. Behavior can be a very helpful gauge of how the baby is feeling. Attempt to calmly soothe the baby.

- Follow-up care. Instructions for seeking further medical evaluation after the initial reaction. This should include detailed communication with healthcare providers.

- Emergency contact information. Essential contact numbers for the infant’s pediatrician and local emergency services.

Dr. Pistiner recommends using AAP’s Action Plan

What should be part of an Emergency Anaphylaxis Action Plan for infants?

The Emergency Anaphylaxis Action Plan (or Allergy and Anaphylaxis Emergency Plan) should be filled out by primary care doctors and allergists alongside parents.

The action plan can be used in daycare settings. The document provides an excellent foundation to learn, follow, and teach secondary care providers who you are entrusting with your infant with a food allergy.

Review the AAP action plan and think about the nuances when it comes to the anaphylaxis management of infants. The current plan highlights the severe symptoms that you would treat. Consider using infant-specific terms (reported in a survey of caregivers who witnessed their young child’s severe allergic reaction) when discussing anaphylaxis and when teaching others.

Follow-up care and diagnosing infant anaphylaxis

Many parents find out their child is at risk for serious allergic reactions after an allergy diagnosis or an anaphylactic event. Seek follow-up care and work with your child’s healthcare team to determine the cause of the allergic reaction. Then establish a plan to avoid triggers and treat subsequent reactions.

The healthcare provider may ask for a detailed history of symptoms, including:

- feeding behaviors, such as refusal to eat or fussiness

- exposures to potential or known allergies (foods, medications, insect venom, latex, or environmental triggers)

- family history of allergies

- preexisting atopic conditions such as eczema or asthma

This information helps doctors determine patterns from the reaction and identify likely triggers.

Your doctor may conduct diagnostic tests to pinpoint specific allergens. These may include skin prick tests, blood tests, and serum-specific IgE measurements. Doctors may also recommend an oral food challenge. This can help confirm a food allergy diagnosis and evaluate its severity. An oral food challenge should only be done in a healthcare setting under the supervision of a doctor.

Dietary management considerations

It’s important to note that unnecessarily removing foods from a baby’s diet can affect how their immune system learns to tolerate different foods. This could increase the baby’s risk of developing food allergies. Any changes to a baby’s diet should be made with the help of a pediatric allergist.

What comorbidities complicate diagnosis and treatment?

Some health conditions can make it harder to diagnose and treat allergies. For example, babies with eczema often have other allergic conditions in a pattern called the “atopic march.” This means that early eczema or food allergies can lead to asthma or allergic rhinitis later in life.

Each of these conditions share similar symptoms and they can sometimes overlap with symptoms seen in an allergic reaction. This can make it even more difficult to recognize allergic reactions or anaphylaxis.

Work with your doctor to learn what signs and symptoms to look for in your baby. Regular check-ups are important opportunities to get comfortable managing allergic issues with your child.

Questions and answers (Q&A) on infant anaphylaxis

Here are common questions we are asked about anaphylaxis in infants and young children. If you have any other questions you would like to see answered here, please email our editor.

Reviewed by:

Michael Pistiner, MD, is a pediatric allergist and the Director of Food Allergy Advocacy, Education, and Prevention at Mass General Brigham for Children, Harvard Medical School, Boston. He specializes in food allergy and anaphylaxis prevention and management in infants and toddlers. Dr. Pistiner’s team has proposed modified criteria for identifying anaphylaxis in young children and developed the Food Allergy Management Prevention Clinician Support Tool for Infants and Toddlers (FAMP-IT.org) to help primary care providers prevent and manage food allergies in this age group. Dr. Pistiner is a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Allergy and Immunology, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, and Chair of the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Anaphylaxis Committee.